Written by: Chung Tử Linh-Thao

An argumentative reflection from a second-generation Vietnamese Christian. Views expressed in the article are not necessarily that of TLC but rather for the purpose of in-house reflection.

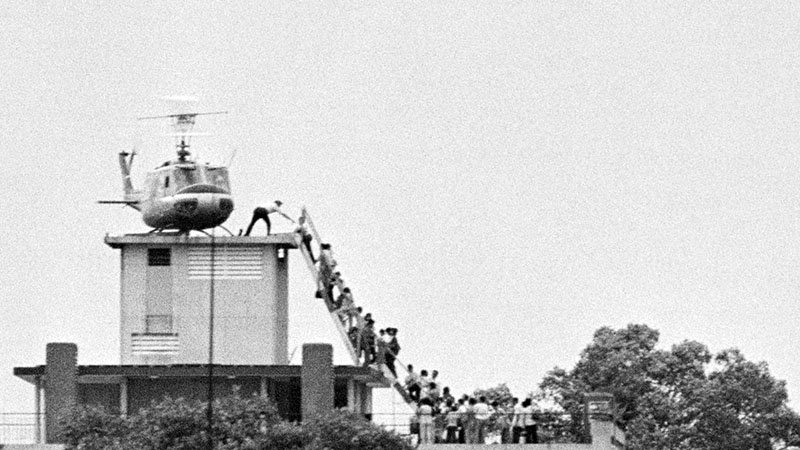

The Fall

April 30th, 1975. The People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and their Viet Cong allies capture Saigon, then capital of South Vietnam. The flag of the National Liberation front of Vietnam is flown over Independence Palace (now Reunification Palace) ending the Vietnam War and reunifying the country, where it will soon be replaced by the Socialist Republic of Vietnam’s flag as the Vietnamese Communist Party reveals its true colors. Saigon is then renamed Hồ Chí Minh City (HCMC) after their revolutionary leader. This ‘reunification’ and the events that follow it, sets off waves of Vietnamese refugees to Europe, Australia, and America where they now make up the majority of the modern Vietnamese diaspora (Việt Kiều).

The Fall of Saigon, as it is known to most Việt Kiều, was the latest climactic event in Vietnamese history, ending a decades long struggle—a result of the intersection between the West’s Cold War and the deep Vietnamese desire for independence following oppressive and paternalistic French colonialization. The Vietnam war brought the spotlight onto the relatively obscure and small Asian nation at a time when extensive and fast paced media documentation became widespread. This combination of factors cemented the connotation of the term ‘Vietnam’ into the world’s memory as yet another example of a Cold War conflict, stained with the deep pain and loss of an entire generation of Vietnamese people who had lost their home, both within and outside of the country. Somehow, however, this small nation had thwarted the military might of America, and had won the ‘American War’ as it was known to the Vietnamese.

Modern Times

This year marks the 46th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon. Second generation Vietnamese individuals like myself are now young adults or are having their own children. A natural question comes to mind: what will we teach our children about the war, and what will this event mean to them? The outlook is depressing. The Việt Kiều of my generation hardly know of Vietnamese history. Their knowledge is limited to parades featuring South Vietnam’s three striped flag, a few Vietnamese dishes, and a modest understanding of Vietnamese. The war obsession of our parents has left us only with a broken collection of decontextualized symbols, festivals, and increasingly inconsequential war trivia as our cultural heritage. Perhaps it is unsurprising that our staunchly anti-communist and conservative parents find that their children are nearly all politically and economically left leaning, heavily assimilated, and Vietnamese in name and skin tone only. Even The Sympathizer, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s Pulitzer Prize winning book featuring Vietnam, is about the war and its aftermath.

Why should it matter anyway? The sentiment that best represents my generation is that “what’s done is done, history is history.” Holding onto the past is at best a quirk and at worst a bad habit of the first generation—a generation they find harder and harder to relate to both culturally and politically. With the wealth and privileges that the West offers, why would they choose to remember a history that they are neither particularly interested in or proud of? Their concerns now center around a Western set of problems and solutions. My generation wants to accrue recognition and social capital in Western institutions as a way to answer legitimate grievances experienced via racism and sociocultural ostracization. To that end, second generation Vietnamese take on a new banner, along with their Chinese, Korean, and other Asian counterparts in the Western Asian Diaspora (WAD). Compared to the first generation WAD, the second generation WAD has their own paradigms. Their battles include fighting for media representation, addressing stereotypes such as the ‘Model Minority,’ and condemning the fetishization of Asian women and emasculation of Asian men. Much of this discourse now occurs in the Subtle Asian Traits Facebook group. The largest Facebook group globally (~2 million members at the time of writing), the sheer volume of members shows the WAD’s deep desire for a cultural outlet in this truly unanticipated cultural phenomenon.

Interestingly, this new banner contains little in the way of actual culture. Instead, it features a shallow, Westernized political characterization of a nebulous, ill-defined group known as “Asian.” Cold War era transplant parents of the WAD might be reasonably horrified that a significant and enlarging theme in this banner centers around diversity (critical theory), equity (oppression), and inclusion (privilege). These are ideas which are either indirectly or directly inspired by Marxism—the very reason why many of us find ourselves in the West in the first place. Is history repeating itself?

After a century of Western hegemony and imperialism, followed by widespread humiliation from their Japanese cultural sibling, states in the East fought back. Groups in China, Vietnam, and Korea, among others, adopted another ironically Western idea, known as Marxism, usually under the guise of nationalism. Communism, like other movements, was used to rally the political momentum needed to expel their respective colonizers, but paradoxically led to a series of civil wars. The Chinese Civil War, Vietnam War, and Korean War, by some cruel twist of history, pulled Western powers back into Asia where the majority of lives were lost, blood was spilled, and munitions were spent in the Cold War. In everywhere but half of Korea, Communists would expel all political opposition, real or imagined, with a crimson fervor unmatched by their colonial predecessors. Once a communist regime took power, its first project invariably consisted of historical revisionism, cultural deterioration, and violent political repression. Escaping conflict and tyranny, a large number of Asians fled to Western countries, especially America, where they joined others who had earlier relocated in search of a better life.

The WAD’s attraction to Marxist ideas is symptomatic of our historical illiteracy. We seek to distinguish ourselves in the West but simultaneously lack a well-defined cultural foundation to do so. Western cultural norms such as individualism and an obsession with external appearances are in such stark contrast to Eastern collectivism and humility, that a great deal of the WAD never experience the beauty and complexity of their native cultures and history. To add insult to injury, expression of Eastern values in the West is actively discouraged and punished. As Asians, we were stigmatized for our appearance and isolated from our history. Even when we became ‘popular’ enough, we were expected to stay in a sociological niche defined by our skin color rather than our personalities. Though the WAD had a brief Renaissance on YouTube, it was clear that we were still seen as ‘other.’ As a result, several social phenomena became common among the WAD, three of which I describe here:

- Many of us have come across those we would label as “white-washed”—a colloquial term denoting ethnically Asian individuals who intentionally assimilated themselves and did their best to avoid being in an ‘Asian bubble.’ They shared little in the way of culture besides appearance and unremarkable culinary preferences due to unhealthy or apathetic attitudes about their native culture.

- Others, including myself, have distinct experiences of being the ‘Token Asian,’ where our inclusion in a group of non-Asians is maintained privately for the sake of our apparent novelty (or exoticness) and publicly as a shallow marker of diversity.

- The Asian Bubble is a phenomenon where WAD individuals, especially those from historically Confucian countries, have social networks that consists almost entirely of other individuals from the WAD. Because of a mutual cultural affinity and ostracization in Western society (in part due to the strong aromas of our cuisines) many of us found a refuge with each other.

These phenomena are symptoms of a common Western mindset and attitude regarding minority cultures, but I find it important to mention because of the unique dynamic between Confucian and Western values. Historically, this is not new. In Asia, we also had our share of colonial sympathizers and treatment as second class citizens.

Although I believe these descriptions are still accurate and relevant, they are already outdated. In the 90s, Asia rapidly increased it’s economic prosperity, best demonstrated by the many Asian Economic Miracles that happened during that time. Riding the current of globalization, the WAD have also gradually gained more cultural capital and breathing room. Now, we are less prone of being automatically ashamed of our heritage. In other words, if your family’s country of origin is no longer considered ‘Third-World,’ then there is one less thing for the Westerners to look down on. Furthermore, many Asian countries not only became significant economic competitors, but also began their own substantial cultural exports. These include Hong Kong’s martial arts (Bruce Lee), Japanese media (Manga and Anime), the latest addition: South Korean media (K-Pop and K-dramas) which have all accompanied an explosion in the popularity of various Asian cuisines.

These exports used to be an exclusive, niche shared cultural experience of the WAD. It gave us a connection to something living which we did not previously have in the West and more importantly, something to be proud of. For many in the WAD, Ghibli was our (arguably better) alternative to Disney, and Milk Tea was our alternative to Starbucks. To this day, this cultural produce solidly remains the de facto lingua franca of the WAD, along with memes illustrating our parents’ archaic but amusing behavior. In fact, what was embarrassing to admit to enjoying, is now normalized and ubiquitous. Not only have MMA, K-Pop, Anime, and Phở entered into common lexicon in the Anglophone world, but also enjoy broad international popularity beyond the West.

Still, there is an obvious asymmetry. There have been little to no cultural exports from current communist regimes such as China, North Korea, and Vietnam. Even among the WAD, it was not uncommon to find Chinese and Vietnamese individuals who wished they were either Korean or Japanese. The effect of communism on culture is clear, if it had not already been made clear through Mao’s Cultural Revolution, Kim Il Sung’s Songbun, and Ho Chi Minh’s bloody land reforms. Marxism replaces culture with simplistic economic categories into which human beings are frantically classified as good or evil. Then, people are judged based on the feverish, often manufactured, resentment of a horde of revolutionaries. In Asia, Communism’s bloody rejection of Confucianism has left no shortage of suffering. Vietnam had an extra handicap, as France pulled it out of the East Asian orbit during the colonial era, by attempting to Westernize Vietnamese institutions and culture.

The most visual example is Vietnam’s Latinized script Quốc Ngữ. Although Quốc Ngữ improved literacy rates in Vietnam, it effectively alienated the Vietnamese people from the rest of their history written in Classical Chinese and Chữ Nôm. This separation has been so complete that few people, even in the Việt Kiều, associate Vietnam with East Asia. Instead, it has become common to think of Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia when Vietnam is mentioned, of which it shares little in common besides climate and land borders, let alone culture. When communism was imported to Vietnam, Vietnam was reduced to a backdrop of another proxy war between America and the USSR in the eyes of the world. Vietnamese culture was buried in the drama of the 20th century, after it had already been bled by the French. For example, unlike other Asian countries, mentioning Vietnam immediately evokes thoughts of the war, rather than its culture. At least Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan now have a distinct cultural footprint that is not so obviously obscured by the Cold War.

And unfortunately, the growing prominence of Asian countries and cultures has not afforded the WAD a meaningful cultural literacy. Instead, they are more willing to identify with the idea of being Asian, or whatever the hollow, Westernized picture of being ‘Asian’ means. What used to be shame or silence has transformed into indignance. The most common symptom of this behavior is identifying with one’s ethnic or racial group only when some type of oppression is occurring. There is little to no evidence of cultural or historical critical thinking. Many in the WAD play an enigmatic color-code game where their skin color is only useful for identifying prejudice, or alternatively, something to be used as a cheap social novelty. If you only adopt your cultural or ethnic identity when a Westerner disrespects it, then does it have any meaning outside of that context? If your ‘culture’ is only a tool to bite back at those who offend or hurt you, what depth does it have? Since when did politics become a valid replacement for culture and identity?

Unsurprisingly, this problem is most pronounced in the Việt Kiều, where they can identify themselves as Vietnamese, but do not know that they are Kinh, let alone anything current or historical about Vietnam itself. In a way, they are like their parents, some of whom still plan on overthrowing the current communist regime in Hà Nội. The first generation has become so entranced with this historical battle, that they have lost the battle of the future with their children. My generation, like their parents, have confused politics with identity. They have become politically possessed, forgetting their culture in the process. Perhaps it is through no fault of their own, given their fractured cultural inheritance from an unfortunate history.

What the Fall of Saigon should really represent for Vietnamese people, is a loss of a deep historical and cultural heritage, due to forces beyond our control or our own willful ignorance of the past. Yet, my people readily adopt Westernized identities, problems, and solutions. In doing so, they completely miss the true Vietnamese desire for independence that has historically characterized our strength of will under Chinese domination, French colonialization, Japanese harassment, and American geopolitics. If my people are ready to forget their culture; if the majority of my generation have “mất gốc,” then must Saigon also fall in the West?

A Different Story

The Kind Magistrate

In a small corner of Vĩnh Long, somewhere in the vicinity of the Mekong, an American missionary is navigating the terrain accompanied by a pastor who is also his translator. Like so many places in Vietnam, Thành Lợi is humid, rural, and dedicated to agriculture. Here, between large swaths of rice paddies and groves, the natives go about their lives quietly. Their day to day activity is a humble cycle of work, livelihood, and occasional, but inconspicuous political subterfuge. Being so far in the south, it is a relatively recent addition to Vietnam, following imperial acquisition in a war a century ago. Americans would eventually have a heavier presence here and in many other places, but right now, France still grips her colonial possession tightly.

The American’s presence is unusual. In the Far East, he is a stranger far away from home. As he travels from estate to estate, he is greeted with suspicion and skepticism. Evidently, he is not welcome here. Neo-feudal magistrates, along with their tenants, have no desire to hear what he has to say. To them, he is an untrustworthy foreigner trying to spread his peculiar Western philosophy. Again and again, his requests for an audience are denied and he is asked to remove his presence from their land. It was a rather strange location for him to be, objectively speaking. What was this Westerner doing in such an obscure location in this nation that had already been commandeered by the French? Presumably, some Catholic priest had already made his rounds or perhaps Thành Lợi was simply neglected. Either way, neither he nor the people here had any obvious incentive to interact.

Still, Mr. Carlson and Tran Xuan Hy, persisted. Not too long after, Nguyễn Ái Quốc would send a telegram. to Harry S. Truman asking for America’s assistance in Independence negotiations with the French. Although the Americans would end up ignoring the telegram, here Mr. Carlson was being ignored by the locals. What did this American want to share so badly that he would endure being rejected by the people that his government found convenient to ignore? It could have been that his efforts too, were in vain, until he and the pastor came upon the expansive estate of Le Ngoc Diep.

Hearing of this visitor from a foreign land, Le Ngoc Diep’s interest was piqued. Unlike the other magistrates, Le Ngoc Diep did not immediately dismiss Mr. Carlson and his partner. In fact, Le Ngoc Diep differed drastically from his contemporaries who typically had a heavy handed and exploitative relationship with their tenants. Routinely, magistrates would heartlessly take a large portion of whatever their tenants harvested, uninterested by the suffering and resentment they fostered. Le Ngoc Diep made sure that each of his tenants and their families had more than enough to survive even after taking his portion. While settling disputes and conflicts, it was common for magistrates to take bribes. Le Ngoc Diep on the other hand, refused to take bribes when mediating between his tenants—a duty he performed with a distinct calmness, impartiality, and discernment.

Le Ngoc Diep had a much beloved daughter, Le Thi Hue Nhung. As his eldest daughter, she was shuffled in between a set of mothers and many siblings. This led to her gradually, but diligently adopting the majority of household responsibilities, in addition to assisting her father with estate management. Taking after her father, Le Thi Hue Nhung also cared for the wellbeing of the villagers. Navigating in the flooded rice fields with a small canoe, she would deliver food, medicine and care for sick and injured tenants under her father’s jurisdiction. Also known for being a fantastic cook, Le Thi Hue Nhung, was adored by the tenants. Because of their virtue and charitability, Le Ngoc Diep and his daughter Le Thi Hue Nhung were deeply loved and respected among all of the tenants of his estate.

An open-minded man, Le Ngoc Diep was curious to hear what new ideas or philosophies Mr. Carlson wanted to share. In an act of respect and hospitality, he invites Mr. Carlson and Tran Xuan Hy into the grand house where he would dutifully give ear to the tenants’ struggles and disputes. Early in the day, Le Ngoc Diep is dressed formally as usual, but this time, it is to listen to Mr. Carlson and Tran Xuan Hy. As he seats his guests and himself, Le Ngoc Diep begins an intense, involved, but amicable discussion with Mr. Carlson with the help of Tran Xuan Hy. Decidedly a man of the East, Le Ngoc Diep periodically spends time calmly and silently assessing the story of mercy and grace which Mr. Carlson is telling him. As they finish explaining the rest of their message, something has changed within Le Ngoc Diep. What Mr. Carlson has labored so hard to convey is not simply a philosophy, but an ultimatum.

This ultimatum, however, is at odds with the inherently unfair colonial ultimatum of the French, to which he has also become a tenant in his own homeland. It is nonetheless, a serious ultimatum of judgement, but moreover, one based on justice and an incredible offer of mercy. It is something so radical and yet so familiar to Le Ngoc Diep. Le Ngoc Diep is told of a God, who rather than flaunting his power, humbled himself out of love for his creation—of a profound offer of grace, conditioned not by his efforts, but in spite of them. He realizes that he too, is a tenant of his own life, beyond simple economic liability to the heavy handed and exploitative French. Instead, he is a tenant that has become accountable to the moral debt of his actions. More than Le Ngoc Diep, the magistrate of this relationship righteously demands a payment which he cannot afford. But, in a divine act of mercy the magistrate himself fronts the cost of his debt, by offering his only son, to adopt the tenant into his own family.

After the hour hand on the clock has made significant progress, Mr. Carlson now asks Le Ngoc Diep if he is willing to accept this message. In what must have been a surprising break in his apparent stoicism, Le Ngoc Diep agrees. To confirm if he truly understands, Mr. Carlson and Tran Xuan Hy ask him to join them on their knees to say a prayer, which Le Ngoc Diep also agrees to do. For someone of his standing, Le Ngoc Diep’s decision to lower himself was an unambiguous signal to Mr. Carlson and and Tran Xuan Hy that he both understood and accepted their message.

Le Ngoc Diep would go on to allow Mr. Carlson to use the grand house as a place to study the Bible, as well as a place for education—something usually reserved for the wealthy and privileged. Soon, he would also call on all of his children to hear this same message, encouraging them to accept this new philosophy. Le Thi Hue Nhung in particular had married, moved to the comparatively urbanized Cần Thơ with her husband, and had had children of her own. When she and her family arrived at her father’s estate, Le Ngoc Diep explained the message to them, and Le Thi Hue Nhung also believed. Her husband, Doan Hung Tuong, a respected member of the intelligentsia, did not accept this message, but was not antagonistic.

With a newfound joy, Le Ngoc Diep would help to fund a church, Hội Thánh Thành Lợi, where it still stands today. He would also survive both the Hòa Hảo and Viet Minh insurrections, although they were mutually enemies, they also had a mutual hate of French employed magistrates. While all the other magistrates were summarily executed by Hòa Hảo or Viet Minh mobs—mobs that included their former tenants, Le Ngoc Diep’s tenants refused to turn on him and fiercely defended him instead. Fragments of what comprised his previous expansive estate, as well as people who are familiar with his family still dot the region around Thành Lợi, unlike many others. Le Ngoc Diep’s modern legacy has continued even outside Vietnam, although not without difficulty. Le Thi Hue Nhung’s children all came to accept their grandfather’s belief in Christ in their own personal ways, even in the turmoil of the unfolding civil war.

The War and the Aftermath

The war, which shattered and tore apart many lives and families, tested the faith with which this family had only so recently adopted. As their mother, Le Thi Hue Nhung, tragically passed away at an early age, Doan Hung Lan and his siblings were thrown into the reality of war. Doan Hung Lan, who now had his own children, served as an officer in the South Vietnamese Army (ARVN) in the early years of the conflict. With the steady loss of American support, the tide unambiguously began to shift in the North’s favor. Soon, Doan Hung Lan and his family found themselves trapped in Đà Lạt where he had been stationed. Having heard of the recent PAVN massacre at Huế, where Communists performed their characteristic ‘cleansing’ of certain social classes in the old administrative capital of the Nguyễn dynasty, he was in an increasingly dire position.

Caught in between the rapidly approaching PAVN in the north and Viet Cong forces littering the roads south, masses of people gathered at the airport in Đà Lạt in abject desperation. Attempting to escape by foot to Saigon, the sole remaining stronghold of the ARVN, meant almost certain death. Staying in Đà Lạt was also not an option, as the PAVN had demonstrated their intent in Huế. Standing in military uniform with crossed arms in the airport saturated with people, Doan Hung Lan was clearly out of options. There were few planes left, and fewer tickets still, not that they could have been purchased at any price. Like his grandfather, he maintained a stoic demeanor, not showing any obvious emotion even in this situation. It was not until he received an unexpected tap on his shoulder.

“Anh Tư!”

It was a younger cousin of his, and a pilot who up until this point, flew round trips in between Da Nang and Đà Lạt. He recognized Doan Hung Lan because he was also one of Le Ngoc Diep’s grandchildren. This cousin shouldn’t have been there. Most people who had a means to escape already did, and turning back was practically suicide. Besides, he had no way of knowing that Doan Hung Lan was at the airport. Yet, here he was, by some miracle. It seems that God was not yet done with this family. However, there was a problem. Even with two airplanes provided by his cousin, there was an extremely limited amount of space. He quickly decided to let his wife, children, and a few relatives board the planes which could not safely carry any more passengers. Doan Hung Lan stays in Đà Lạt while his family is transported to Saigon in what would be a brief respite. Đà Lạt eventually ends up in the hands of the PAVN during the Tet offensive, but is held only shortly before returning to South Vietnamese control. Unfortunately, this won battle, was the exception, rather than the rule.

A few years later in 1975, Doan Hung Lan is reunited with his family, but now he is in a similar situation in Saigon—which falls within a week of his arrival, as the last of the American forces evacuate. An opportunity to escape materializes, as his younger brother Doan Hung Quy makes preparations for the entire extended family to flee. Doan Hung Lan chooses to stay believing that there had to be another solution, but this turns into a mistake that he would pay for dearly. He, his brother, and other former members of the South Vietnamese military, government, and bureaucracy are led to believe that they will spend 10 days in ‘Reeducation.’ This 10 days, which transforms into 7 years for Doan Hung Lan, and even longer for others, leaves him nearly completely paralyzed. Having paid such a heavy price for his decision to stay, his belief that there may still have been a political solution for Vietnam may have been thoroughly discarded by the Communists, but his belief in Jesus did not waiver, even through 7 years of Reeducation.

Having missed the first wave of escape from Vietnam, Doan Hung Lan and his family would witness the Communist Party’s gradual transformation of Saigon from a beacon of prosperity into a paradise of Leninist socialism. Still, God was not finished with this family. After a little over a decade, all of Doan Hung Lan’s children, many now married themselves, would find their way out of Vietnam. He and his wife would eventually join them in America.

Refugees in a Foreign Land

Le Ngoc Diep’s descendants now find themselves in Mr. Carlson’s homeland. In temperate Orange County, the largest concentration of Vietnamese people outside of Vietnam reside. From Saigon in Vietnam to little Saigon in Westminster, a lively ethnic enclave of Vietnamese people is establishing its presence. Little Saigon makes it presence known with small houses with haphazard arrangements of plants in varying degrees of health, often surrounding a mysterious fruit tree. For wealthier residents, the houses are a characteristically tacky combination of Buddhist temple and French Baroque building, sometimes with a stone lion or two to greet you. The streets are scattered here and there with reckless drivers that are so anxious that they drive as if they had no fear at all. Around you, there are plazas with restaurants and offices perpetually stuck with Saigon’s early 1970s aesthetic. The Asian Garden Mall has recently begun construction.

The ethnic enclave, although not particularly wealthy, is highly interconnected. The collectivism of the homeland is facilitated through various organizations like ethnic churches. Communists, being no friends to Christians, had a special talent for giving them bountiful reasons to leave. Hong Bich Doan, Dong Hung Lan’s wife, who has recently immigrated from Vietnam, is caring for her grandson of 1 month, relieving the burden for her daughter and son in law who like other immigrants, have a dizzying and intimidating array of work, school, and parenting. Doan Hung Lan is mostly resigned to a bed, where Hong Bich Doan continues to care for him as well. Thanks to his grandmother’s inability to speak English, Linh-Thao Chung would speak Vietnamese for many years before he finally begins to pick up English from Barney, Sesame Street, and Kids WB. I would only later realize that I first started learning English from a purple dinosaur.

It also took me a while to understand why the other silly kindergartners could not speak Vietnamese until I was horrified that the teacher could not speak it either. I was also delighted when we had in-class math assignments, because it meant that I had my choice of playground items, well at least until the pesky Korean girl who finished shortly after I did started to follow me around. If you are that person and find yourself reading this somehow, then I would like to apologize for telling Mrs. Mercurio that you were bothering me. I will forever admire that you were never bothered by how much we were teased for being an item by the others, because I also had to instruct my grandma to not kiss me after she dropped me off since it was embarrassing. Vietnamese being the least of my worries, there were so many glaring differences that took me a long time to put words on. According to the other kids, I was ‘Asian,’ whatever that meant. All I know is that the bowl cuts were not my style and that mom needed to know that my hair texture was a problematic novelty. The other kids and teachers rubbed the back of my head in admiration of the sensation that the uniformity of my black hair imparted on their hands.

More and more, I slowly began to realize that my people are a complex combination of extremes. We are warm and loyal and also envious and materialistic. We can adapt to almost any set of circumstances but suffer so many layers of mental health issues. We are incredibly enthusiastic and conscientious but also seem like we are always on the edge of an identity crisis. We are universally united by our by ability to be endlessly tacky and still complain about virtually anything. And by tacky, yes I am talking about Cai Loung and the electronic keyboard—forever the scourge of Việt Kiều music. The adults never seem to get tired of you two—you two only survive because they are hopeless romantics.

Asian and Christian

Most of us ‘Asians’ realized that there was something to this label. It was a little hard to ignore, given the distribution of hair color in the universities. Was this supposed to be a running gag that we all agreed to keep going? If it is, we are doing a good job, maybe too good. And why do I keep running into you guys in church? We are already overrepresented in the campus, what’s the point of doing it again in the college ministries? Who are we trying to fool there? Wasn’t this supposed to be a Western religion? If this is a game, we are seriously overachieving—there are too many of us in Subtle Christian Traits too. Oops, “over-achiever” might bring up some bad memories for a lot of us. But, we are doing it so well that the term for Pastor in Chinese, Vietnamese, and Korean are essentially the same. Look, I know that our Korean brothers and sisters in Christ have been faithfully planting churches ever since they got here, but I am dying to know when we can finally address the elephant in the room about our curious ability to find each other.

Whatever ‘Asian’ is supposed to mean is probably never going to be resolved, but I do know that in our ethnic Churches and Asian American Churches, we can be ‘Asian’ without worrying about it being something unnatural. I don’t know what you think of when you hear the word “Confucius,” but at the very least, most of us don’t mind living with our parents and we genuinely want to make them proud. Actually, many of us have a Church to thank for our access to food, history, and language, without which most of us could probably care less. I don’t like being referred to as a ‘Model Minority’ either. What I do know is that the sacrifices that our parents made for us are not random and that the many sacrifices that we made to do well in school are not random either. We have cultures that value sacrifice and honor. Again, ‘Confucius’ probably said something about it, but regardless of whether that is a product of Confucianism or whether we end up being called a ‘Model Minority,’ I still plan to honor my parents and work hard.

Christianity is also something more than just another label we assign ourselves, or the faith that our parents happened to have. Honoring your parents is literally a commandment, and the best example of sacrifice is none other than Jesus Christ. As Asians, Confucianism can tell us a lot about our peoples and our histories, but I also know that it carries a lot of baggage as well here in the West. As Christians, we could at least realize that we have the answer to that: Confucianism is humanistic, but Christianity makes it more than just about ourselves and having a level of honorability. As much as we are afraid of losing face, Jesus already lost face for us. Honestly, we have a unique perspective. Here in the West, especially America, we aren’t White or Black, but we are still Christians. That allows us to see the inherent Western cultural biases that other churches might have. If we say something about Jesus and the Word, then people cannot automatically excuse us as being the stereotypical ‘White Christian.’

The Vietnamese Church

For those of us in the Vietnamese church, I want to tell you that Saigon has fallen, and we should be aware of that and what it means. It’s fallen both in Vietnam and here in the West. But, the Vietnamese church has not fallen. In the Church, culture lives on, planted on a stream of everlasting life. We are not stuck in the past, but following a God who cares about our stories. For the many of you who have left your CMA and Catholic churches: what does it mean to be Vietnamese? I also extend this question to any other Vietnamese person who has the misfortune of coming across my long-winded article. Maybe there is more to the story than getting angry when people are racist towards Asians. If there is more to the story, then where will you find out more about it? Is there any Saigon left for you to do so? Is there a bowl of Phở you can find it in? Is it something to be found in a Korean Drama or a Japanese Anime? God has faithfully continued my family’s story, will you let him continue yours? Doan Hung Lan’s Son, Mục Sư Doan Hung Linh, now pastors a Vietnamese church in Anaheim, where many more stories, including mine, are now continuing.